4 Thoughts as Fitzgerald’s “Paradise” Turns 100

A first novel

still perplexing and astonishing—

and even prescient

- 1st month of F. Scott Fitzgerald reading challenge, 1st novel, This Side of Paradise (1920)

“Amory Blaine inherited from his mother every trait, except the stray inexpressible few, that made him worth while,” begins This Side of Paradise, and we are off and running.

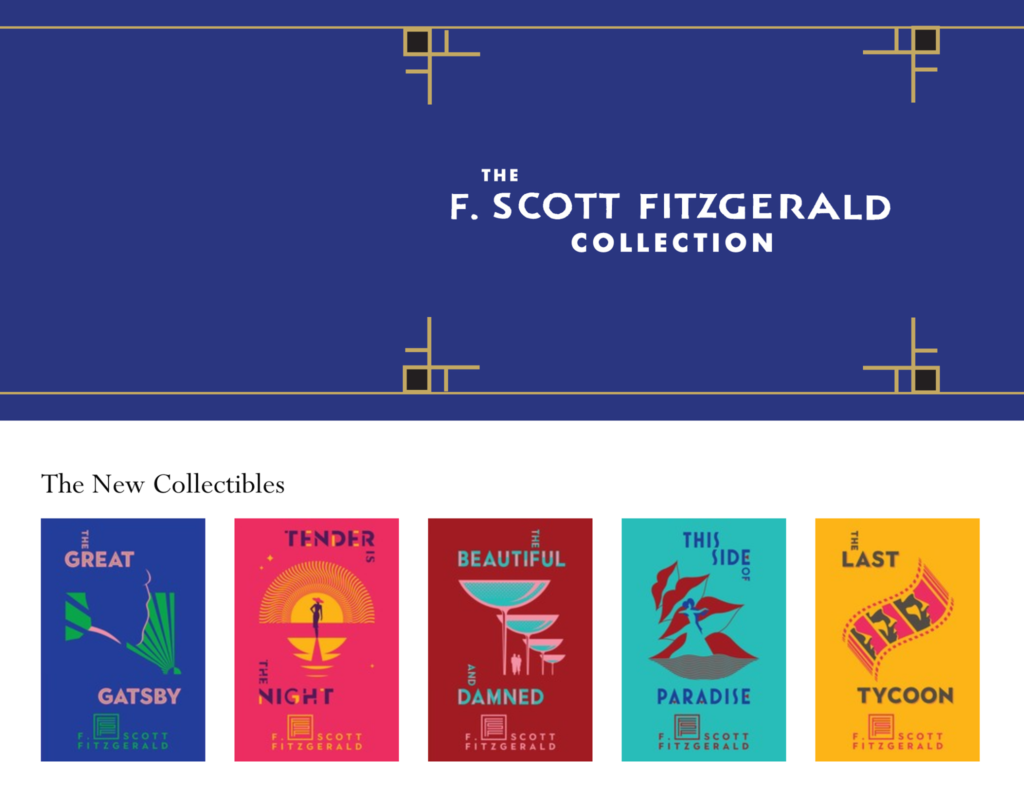

Paradise turns 100 this year and, not surprisingly, this calls for a new “Collector’s Edition” of F. Scott’s Fitzgerald’s first and indeed all his five novels (well, 4½) by his old publisher Scribner, now part of Simon & Schuster. The 100th anniversary of a great author’s first work is certainly cause for celebration, though it seems just as likely that was just an excuse. After all, FSF’s third novel, the insanely brilliant and insanely popular and insanely lucrative The Great Gatsby, slips into the public domain January 1. Scores of publishers, no longer thwarted by copyrights, already have lined up editions for release that very day. Scribner may as well make as much Gatsby money for as long as it can.

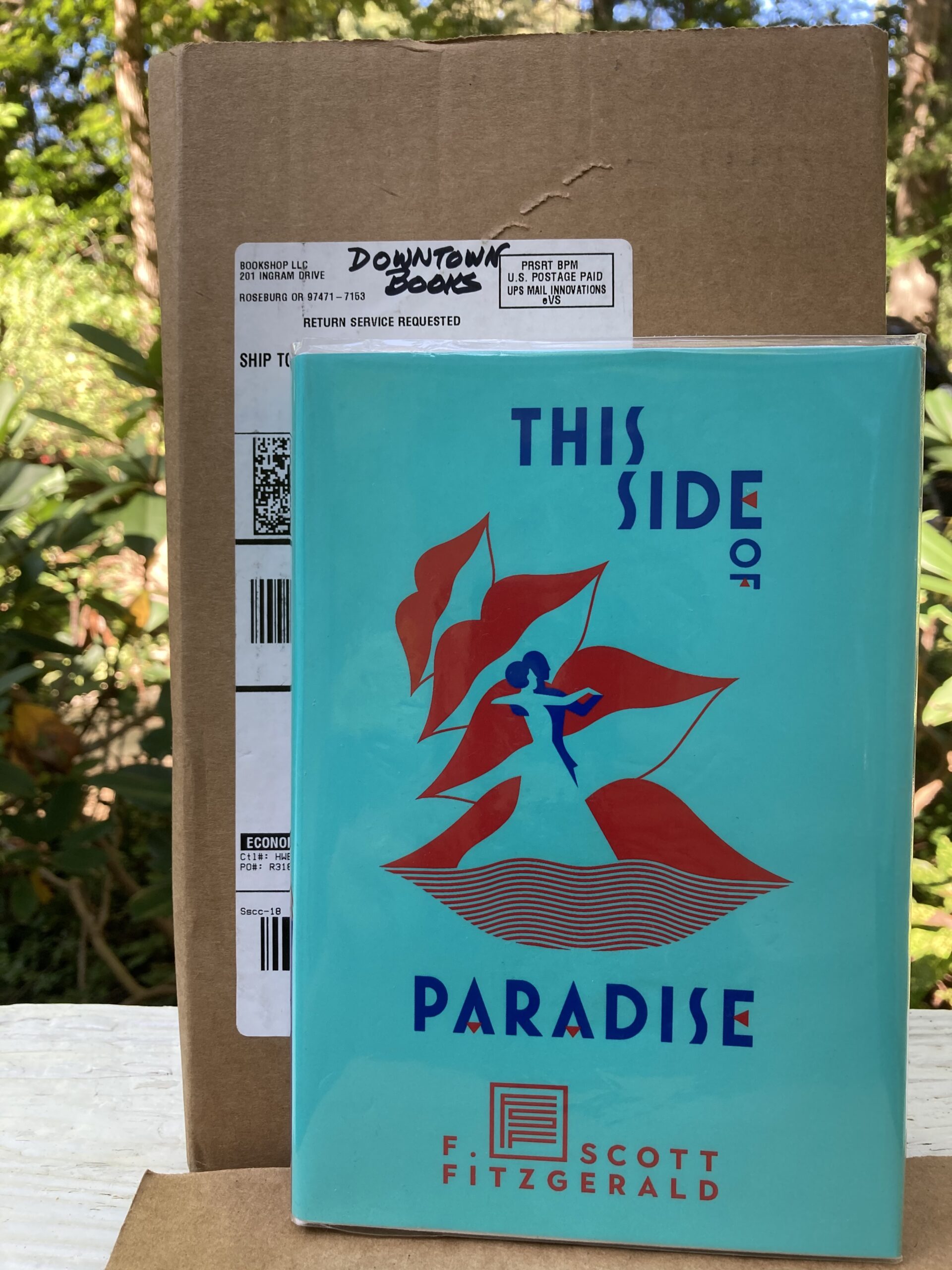

I had only read two of Fitzgerald’s five novels. But these new editions, combined with Independent Bookstore Day on Aug. 29, gave me an excuse. I ordered one each from five of my favorite indies, with the idea of shoehorning one a month into my largely non-fiction reading. (Shoutout here to Downtown Books in Manteo, N.C., for Paradise.)

Four thoughts after reading Fitzgerald’s first.

- NO ASPIRING YOUNG WRITER SHOULD EVER READ PARADISE. EVER. Paradise was written when Fitzgerald was only in his early 20s, bringing together much of Fitzgerald’s early fiction and poetry into a novel. Still a boy, really. It was accepted when he was 22 and published when he was just 23. Paradise nonetheless was a massive success, selling out in three days, and requiring 12 printings totaling 49,000 copies.

It could be disheartening to read. Could anyone emulate this writing at a young age? A few examples, out of hundreds and hundreds in the book:

- “Many nights he lay there dreaming awake of secret cafés in Mont Marte, where ivory women delved in romantic mysteries with diplomats and soldiers of fortune, while orchestras played Hungarian waltzes and the air was thick and exotic with intrigue and moonlight and adventure.” … or …

- “It was a grey day, that least fleshly of all weathers; a day of dreams and far hopes and clear visions. It was a day easily associated with those abstract truths and purities that dissolve in the sunshine or fade out in mocking laughter by the light of the moon. The trees and clouds were carved in classical severity; the sounds of the countryside had harmonized to a monotone, metallic as a trumpet, breathless as the Grecian urn.” …

You get the idea. Read this book as a too-young writer, and you may never write anything again. Not even a postcard. What would be the point?

2. PARADISE IS ABOUT NOTHING AND ABOUT EVERYTHING. The book was famously turned down twice by Scribner (and would have been forever dead were it not for the support of famed editor Maxwell Perkins) before a rewrite was finally accepted. Reason: nothing seemed to happen. On the face, Paradise is a coming-of-age book, semi-autobiographical at times, with the main character going from teenage years through college days at Princeton to service overseas in World War I and then to New York as an advertising copywriter. He has relationships with four girls or women over the years, ending unrewardingly. He has innumerable conversations with friends and, well, everyone.

That’s the plot, people.

But it also a book that has startlingly evocative discussions (and poetry) about love and romance, sex (groundbreaking a century ago), social classes, money and materialism, success, war, idealism, race, poverty, religion, the Catholic church, art, poetry, youth, the current generation, the meaning of life. It is on-target, often thoughtful and captivating, sometimes jaw-dropping. FSF would become the foremost chronicler, and the most dazzling, of his generation.

Offering quotes is silly, but here a few. They’re really more punchlines than discussions:

- “I suppose all great happiness is a little sad. Beauty means the scent of roses and then the death of roses—”

- “Experience is the name so many people give to their mistakes.”

- “I’m a cynical idealist.’ He paused and wondered if that meant anything.”

- “We want to believe. Young students try to believe in older authors, constituents try to believe in their Congressmen, countries try to believe in their statesmen, but they can’t. Too many voices, too much scattered, illogical ill-considered criticism.”

- “Her philosophy is carpe diem for herself and laissez faire for others.”

- “I’m a romantic; a sentimental person thinks things will last, a romantic person hopes against hope that they won’t.”

3. THIS IS A DIFFICULT BOOK. I’m not gonna lie. This book sparkles and it dances, but it also befuddles. It can be difficult to tell what is happening, or even who’s involved. The early organization seems scattershot. The book jumps around in time, as well as from third-person to second-, to stream of consciousness, to poetry, to letters, to conversations both real and imagined.

Two other hurdles: 1. Fitzgerald was exceptionally well-read and intelligent, more so—let’s be honest—than most of us readers. 2. Many people and events he mentions are unknown to us now. Fortunately, there are eight pages of explanatory notes. (The book’s editor, James L.W. West III, is also editor of the 18-volume Cambridge Edition of the Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Cambridge Paradise has 55 pages of Notes, from which these were drawn. … I could have used all 55.)

4. FITZGERALD SOMETIMES SEEMS, WELL, PRESCIENT. From 1920, his novel talks frequently about issues that concern us today: from dictators to religion, from the opposite sex to the meaning of life.

Moreover, he makes references to the future, even a hundred years in the future, which—let’s do the calculations here—yes, would be 2020. One sample:

He wondered that graves ever made people consider life in vain. Somehow he could find nothing hopeless in having lived. All the broken columns and clasped hands and doves and angels meant romances. He fancied that in a hundred years he would like having young people speculate as to whether his eyes were brown or blue, and he hoped quite passionately that his grave would have about it an air of many, many years ago.

More extraordinary was Fitzgerald’s predictions about women and the place they might hold. Even as his main character pursued women, he seemed to find sexual attraction was negating his own good qualities. And what of women? They weren’t equal, but why not? FSF makes no mention of the 19th Amendment, securing women’s right to vote, which was not passed until a few months after Paradise was published. But in 2020, the centennial year of that amendment and the year of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s passing, not to mention the influence of the MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, this all resonates.

Here’s one of the more evocative call-outs to our age:

“Rotten, rotten old world,” broke out Eleanor suddenly, “and the wretchedest thing of all is me–oh, why am I a girl? Why am I not stupid? Look at you; you’re stupider than I am, not much but some, and you can lope about and get bored and then lope somewhere else, and you can play around with girls without being involved in meshes of sentiment, and you can do anything and be justified—and here am I with the brains to do everything, yet tied to the sinking ship of future matrimony. If I were born a hundred years from now, well and good, but now what’s in store for me—I have to marry, that goes without saying. Who? I’m too bright for most men, and yet I have to descend to their level and let them patronize my intellect in order to get their attention. Every year that I don’t marry I’ve got less chance for a first-class man.

A hundred years from now, to quote the passage, and the book still calls out to us. This Side of Paradise may not be a truly great book (although I feel more than a little silly being one to give even modest criticism to FSF). But it’s certainly on the way. You can sense greatness ahead.

And remember … the youngest of men, not much more than a child, wrote it!

I cannot wait for the next four books.

This Side of Paradise (1920), from Downtown Books, Manteo, N.C.

The Beautiful and The Damned (1922), from Buxton Village Books, Buxton, N.C.

The Great Gatsby (1925), from Books to be Red, Ocracoke, N.C.

Tender Is the Night (1935), from Quarter Moon Books and Gifts, Topsail Beach, N.C.

The Last Tycoon (1941). from Fountain Bookstore, Richmond, Va.